Bariatric surgery is an operation on the stomach and/or intestines that helps patients with extreme obesity to lose weight. Severe obesity is a chronic condition that is hard to treat with diet and exercise alone. This surgery is an option for people who cannot lose weight by other means or who suffer from serious health problems related to obesity. The surgery restricts food intake, which promotes weight loss and reduces the risk of type 2 diabetes. Some surgeries also interrupt how food is digested, preventing some calories and nutrients, such as vitamins, from being absorbed. Recent studies suggest that bariatric surgery may even lower death rates for patients with severe obesity. The best results occur when patients follow surgery with healthy eating patterns and regular exercise.

Bariatric Surgery for Adults

Bariatric surgery may be an option for adults with severe obesity. Body mass index (BMI), a measure of height in relation to weight, is used to define levels of obesity. Clinically severe obesity is a BMI > 40 or a BMI > 35 with a serious health problem linked to obesity. Such health problems could be type 2 diabetes, heart disease, or severe sleep apnea (when breathing stops for short periods during sleep).

Who is a good adult candidate for surgery?

Having surgery to produce weight loss is a serious decision. Anyone thinking about having this surgery should know what it involves. Answers to the following questions may help patients decide whether weight-loss surgery is right for them.

Is the patient:

- Unlikely to lose weight or keep it off over the long term using other methods?

- Well informed about the surgery and treatment effects?

- Aware of the risks and benefits of surgery?

- Ready to lose weight and improve his or her health?

- Aware of how life may change after the surgery? (For example, patients need to adjust to side effects, such as the need to chew food well and the loss of ability to eat large meals.)

- Aware of the limits on food choices, and occasional failures?

- Committed to lifelong healthy eating and physical activity, medical follow-up, and the need to take extra vitamins and minerals?

There is no sure method, including surgery, to produce and maintain weight loss. Some patients who have bariatric surgery may have weight loss that does not meet their goals. Research also suggests that many patients regain some of the lost weight over time. The amount of weight regain may vary by extent of obesity and type of surgery. Habits such as snacking often on foods high in calories or not exercising can affect the amount of weight loss and weight regain. Problems that may occur with the surgery, like a stretched pouch or separated stitches, may also affect the amount of weight loss. Success is possible. Patients must commit to changing habits and having medical follow-up for the rest of their lives.*

Bariatric Surgery for Youth

Rates of obesity among youth are high. Bariatric surgery is sometimes used to treat youth with extreme obesity. Although it is becoming clear that teens can lose weight after bariatric surgery, many questions still exist about the long-term effects on teens’ developing bodies and minds.

Mounting evidence suggests that bariatric surgery can favorably change both the weight and health of youth with extreme obesity. Over the years’ gastric bypass surgery has been the main operation used to treat extreme obesity in youth. An estimated 2,700 youth bariatric surgeries were performed between 1996 and 2003.2 A review of short-term data from the largest inpatient database in the United States suggests that these surgeries are at least as safe for youth as adults. As yet, AGB has not been approved for use in the United States for people younger than age 18. However, favorable weight-loss outcomes after AGB for youth have been reported abroad.

The Normal Digestive Process

Normally, as food moves along the digestive tract, digestive juices and enzymes digest and absorb calories and nutrients. After we chew and swallow our food, it moves down the esophagus to the stomach, where a strong acid continues the digestive process. The stomach can hold about 3 pints of food at one time. When the stomach contents move to the duodenum (the first part of the small intestine), bile and pancreatic juice speed up digestion. Most of the iron and calcium in the food we eat is absorbed there. The other two parts of the nearly 20 feet of small intestine absorb nearly all of the remaining calories and nutrients. The food particles that cannot be digested in the small intestine reside in the large intestine until eliminated.

How does surgery promote weight loss?

Bariatric surgery restricts food intake, which leads to weight loss. Patients who have bariatric surgery must commit to a lifetime of healthy eating and regular exercise. These healthy habits may help patients maintain weight loss after surgery.

Types of Bariatric Surgery

The type of surgery that may help an adult or youth depends on a number of factors. Patients should discuss with their health care providers what kind of surgery is suitable for them.

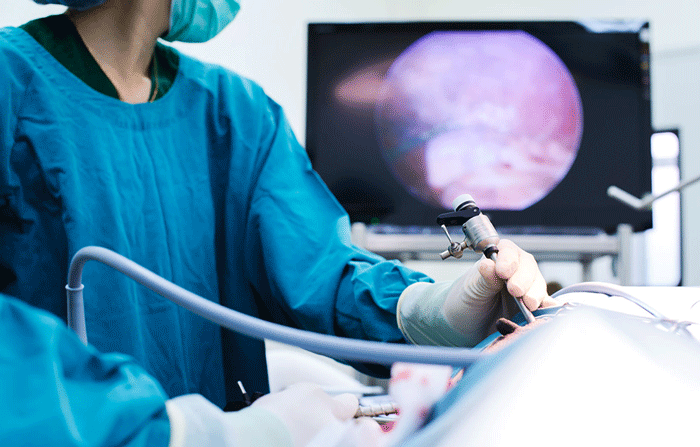

What is the difference between open and laparoscopic surgery?

Bariatric surgery may be performed through “open” approaches, which involve cutting the stomach in the standard manner, or by laparoscopy. With the latter approach, surgeons insert complex instruments through 1/2-inch cuts and guide a small camera that sends images to a monitor. Most bariatric surgery today is laparoscopic because it requires a smaller cut, creates less tissue damage, leads to earlier hospital discharges, and has fewer problems, especially hernias occurring after surgery.*

However, not all patients are suitable for laparoscopy. Patients who are considered extremely obese, who have had previous stomach surgery, or who have complex medical problems may require the open approach. Complex medical problems may include having severe heart and lung disease or weighing more than 350 pounds.

What are the surgical options?

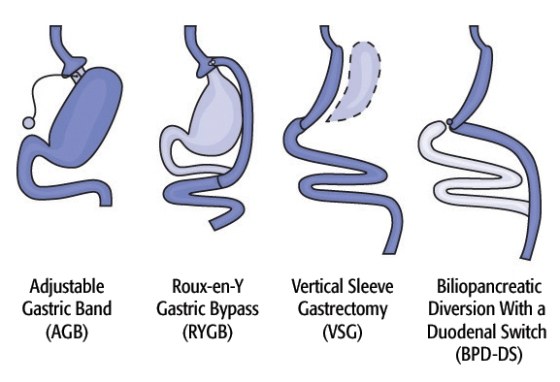

There are four types of operations that are commonly offered in the United States: AGB, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), biliopancreatic diversion with a duodenal switch (BPD-DS), and vertical sleeve gastrectomy (VSG). (See Figure 1.) Each surgery has its own benefits and risks. The patient and provider should work together to select the best option by considering the benefits and risks of each type of surgery. Other factors to consider include the patient’s BMI, eating habits, health conditions related to obesity, and previous stomach surgeries.

Adjustable Gastric Band

AGB works mainly by decreasing food intake. Food intake is reduced by placing a small bracelet-like band around the top of the stomach to restrict the size of the opening from the throat to the stomach. The surgeon can then control the size of the opening with a circular balloon inside the band. This balloon can be inflated or deflated with saline solution to meet the needs of the patient.

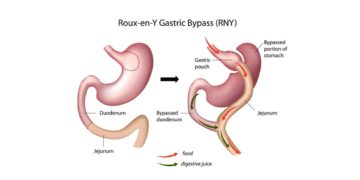

Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass

RYGB restricts food intake. RYGB also decreases how food is absorbed. Food intake is limited by a small pouch that is similar in size to the pouch created with AGB. Also, sending food directly from the pouch into the small intestine affects how the digestive tract absorbs food. The food is absorbed differently because the stomach, duodenum, and upper intestine no longer have contact with food.

Biliopancreatic Diversion with a Duodenal Switch

BPD-DS, usually referred to as a “duodenal switch,” is a complex bariatric surgery that includes three features. One feature is to remove a large part of the stomach. This step makes patients feel full sooner when eating than they did before surgery. Feeling full sooner encourages patients to eat less. Another feature is re-routing food away from much of the small intestine to limit how the body absorbs food. The third feature changes how bile and other digestive juices affect the body’s ability to digest food and absorb calories. This step also helps lead to weight loss.*

In removing a large part of the stomach, the surgeon creates a more tubular “gastric sleeve” (also known as a VSG, discussed later). The smaller stomach sleeve remains linked to a very short part of the duodenum, which is then directly linked to a lower part of the small intestine. This surgery leaves a small part of the duodenum available to absorb food and some vitamins and minerals.

However, when the patient eats food, it bypasses most of the duodenum. The distance between the stomach and colon becomes much shorter after this operation, thus limiting how food is absorbed. BPD-DS produces significant weight loss. However, a decrease in the amount of food, vitamins, and minerals absorbed creates chances for long-term problems.

Some of these problems are anemia (lower than normal count for red blood cells) or osteoporosis (loss of bone mass that can make bones brittle).

Vertical Sleeve Gastrectomy

VSG surgery restricts food intake and decreases the amount of food used. Most of the stomach is removed during this surgery, which may decrease ghrelin, a hormone that prompts appetite. Lower amounts of ghrelin may reduce hunger more than other purely restrictive surgeries, such as AGB.

VSG has been performed in the past mainly as the first stage of BPD-DS (discussed earlier) in patients who may be at high risk for problems from more extensive types of surgery. These patients’ high risk levels are due to body weight or medical issues. However, more recent research indicates that some patients who have VSG can lose a lot of weight with VSG alone and avoid a second procedure. Researchers do not yet know how many patients who have VSG alone will need a second stage procedure.

What are the side effects of these surgeries?

Some side effects may include bleeding, infection, leaks from the site where the intestines are sewn together, diarrhea, and blood clots in the legs that can move to the lungs and heart.

Examples of side effects that may occur later include nutrients being poorly absorbed, especially in patients who do not take their prescribed vitamins and minerals. In some cases, if patients do not address this problem promptly, diseases may occur along with permanent damage to the nervous system. These diseases include pellagra (caused by lack of vitamin B3—niacin), beri beri (caused by lack of vitamin B1—thiamine) and kwashiorkor (caused by lack of protein).

Other late problems include strictures (narrowing of the sites where the intestine is joined) and hernias (part of an organ bulging through a weak area of muscle).

Two kinds of hernias may occur after a patient has bariatric surgery. An incisional hernia is a weakness that sticks out from the abdominal wall’s connective tissue and may cause a blockage in the bowel. An internal hernia occurs when the small bowel is displaced into pockets in the lining of the abdomen. These pockets occur when the intestines are sewn together. Internal hernias are thought to be more dangerous than incisional ones and need prompt attention to avoid serious problems.

Some patients may also require emotional support to help them through the changes in body image and personal relationships that occur after the surgery.

References

1. Inge TH‚ Krebs NF‚ Garcia VF‚ et al. Bariatric surgery for severely overweight adolescents: concerns and recommendations. Pediatrics. 2004 Jul;114(1):217–23.

2. Wilson ST‚ Thomas HI‚ Randall SB. Bariatric surgery in adolescents: recent national trends in use and in-hospital outcome. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2007;161(3):217–221.

This content is provided as a service of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), part of the National Institutes of Health. The NIDDK translates and disseminates research findings through its clearinghouses and education programs to increase knowledge and understanding about health and disease among patients, health professionals, and the public. Content produced by the NIDDK is carefully reviewed by NIDDK scientists and other experts.

The NIDDK would like to thank:

Walter Pories, M.D.‚ FACS‚ Brody School of Medicine at East Carolina University; Thomas Inge‚ M.D.‚ Ph.D.‚ FACS‚ FAAP‚ Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Your Information will never be shared with any third party.

Your Information will never be shared with any third party.